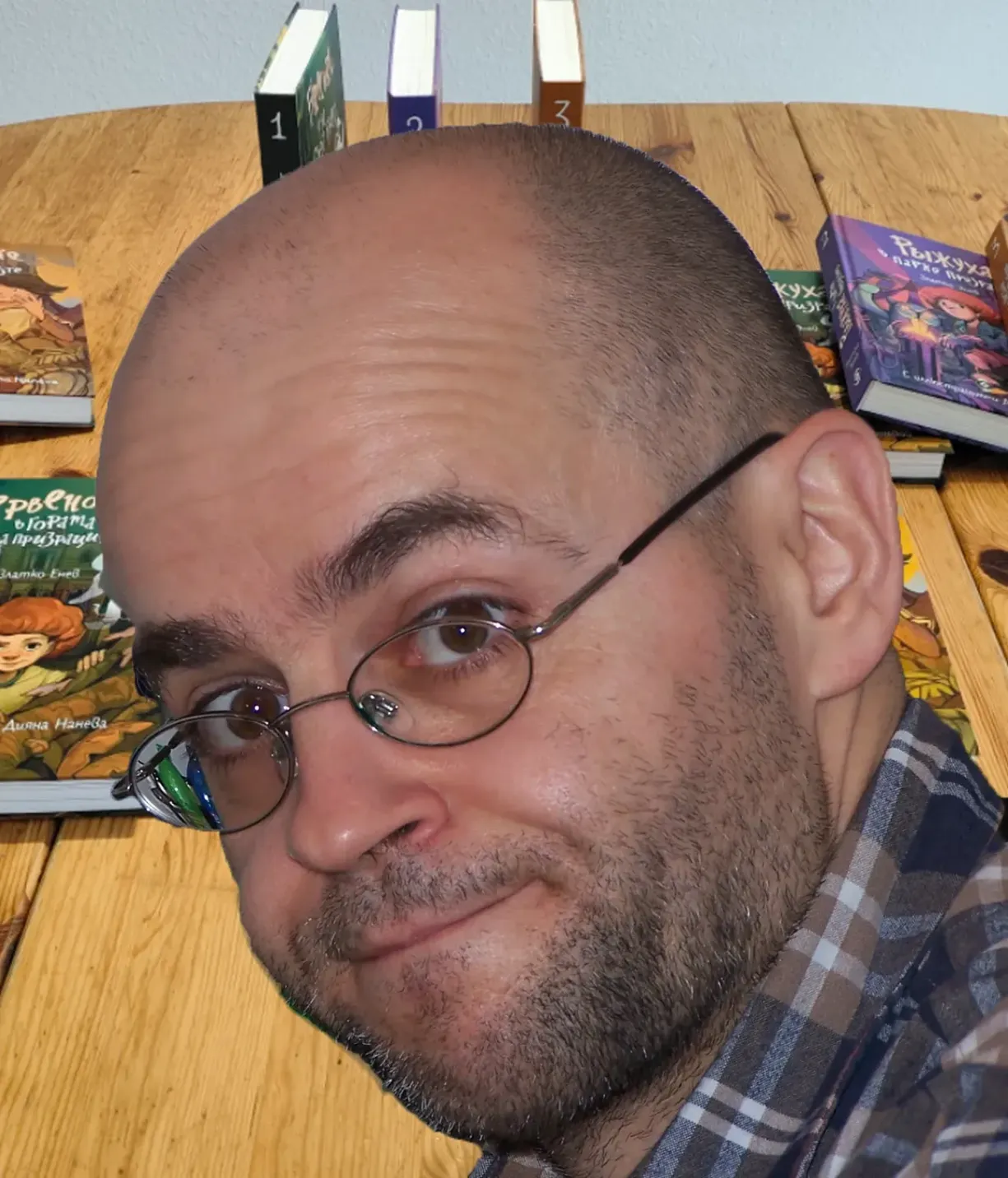

Zlatko Enev:

Profession — Amateur

About the Author

(and the Person)

First and foremost: I consider myself something I call a “professional amateur.”

But what’s the point of such a claim, aside from the obvious wordplay?

You see, a professional amateur is someone who, not by accident but by choice, has opted for a life of constant experimentation an change...

This is someone who doesn’t believe in (or isn’t capable of) gradual improvement in a single professional field; someone constantly accused of scattering their energy in a thousand directions, while their true calling is…

Their only real “profession” is the endless pursuit of the New (the Holy Land, the Holy Grail). Occasionally they impress people with something they’ve done, something others find extraordinary — but at that very moment, their inner voice whispers it’s time to saddle up and move on.

They’ve been rich, they’ve been poor. A caring father (and sometimes a tender lover), but pathologically unable to chase anything except their own dream. Their life is a perpetual string of new beginnings (the small ones constantly; the big ones roughly every ten years). Always busy as a bee. They've created many things (mostly books, not only their own), but the terror of boredom continues to haunt them with the same force it held in childhood.

They are fully aware this probably deprives them of a shot at grand success — but hey, those who know for sure are already dead, so...

“And so it goes,” as another professional amateur — Kurt Vonnegut — liked to say.

But enough of that. Here are the facts, for those who prefer facts to dreams:

Born in Preslav, Bulgaria, in 1961. Studied philosophy at Sofia University during the ’80s. Learned several languages, defended a PhD in 1989. Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, moved to Berlin…

Started a family and professional life (in an entirely new field — book layout and modern publishing tech). Built, from scratch, the full production pipeline for a small academic publishing house. Left the company to launch a solo business in 1995. Earned decent money, got bored, and set off in countless new directions in search of “something.” Became a decent chess player. At the peak of personal and professional boredom, began fulfilling his half-forgotten dream — to be a writer.

Wrote three (beautiful) books for children and adults. Won awards, but never gained wide popularity, even in his home country. Lost most of his earnings during the dot-com crash of the early 2000s. Soon after, lost his family — but kept his children. Kept writing, founded the online journal Liberal Review, now considered the leading intellectual publication in the Bulgarian internet.

Published four more books critical of his home country and its peculiarities — which made him known, but not especially beloved, in Bulgaria.

Still going...

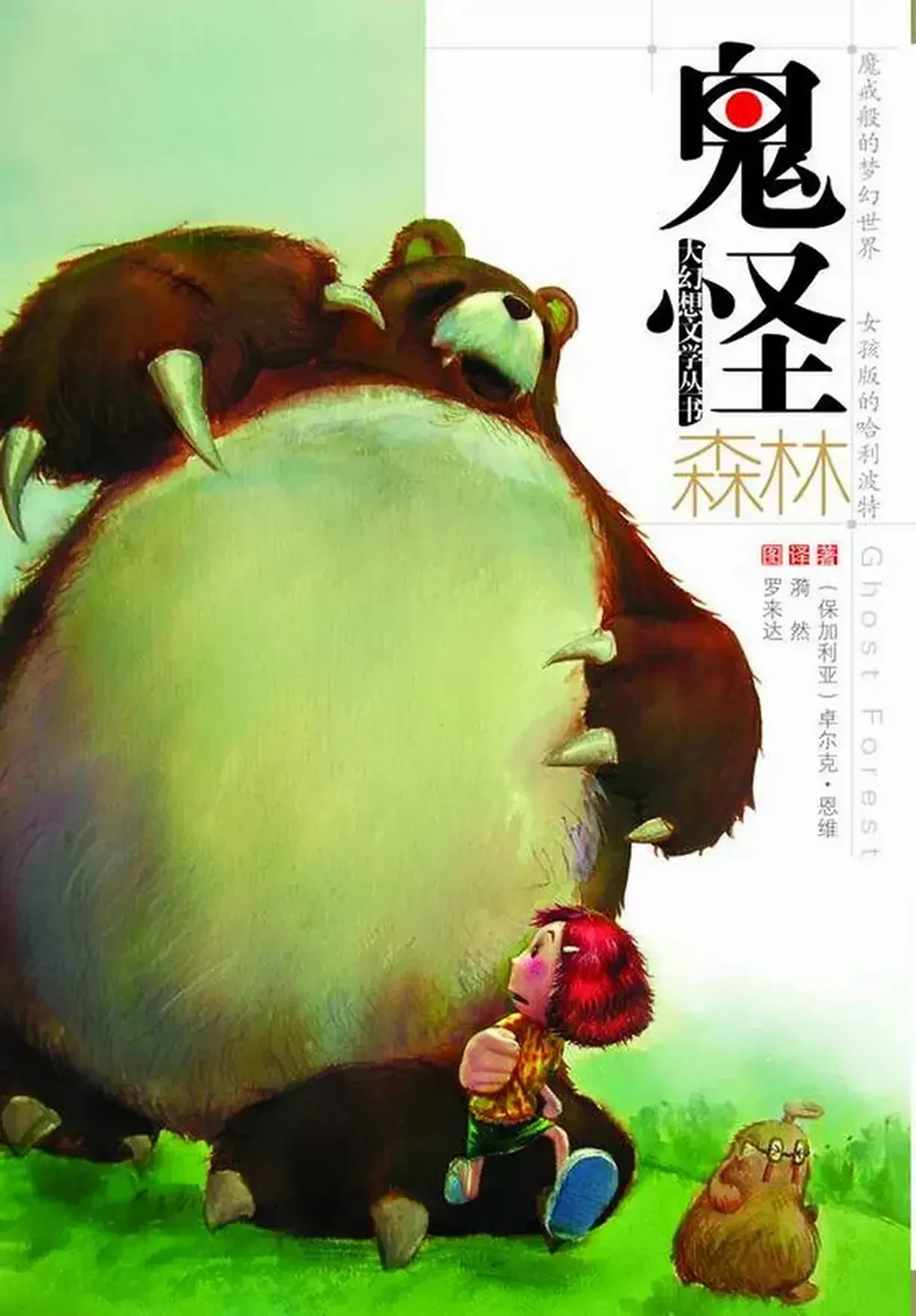

Ghost Forest

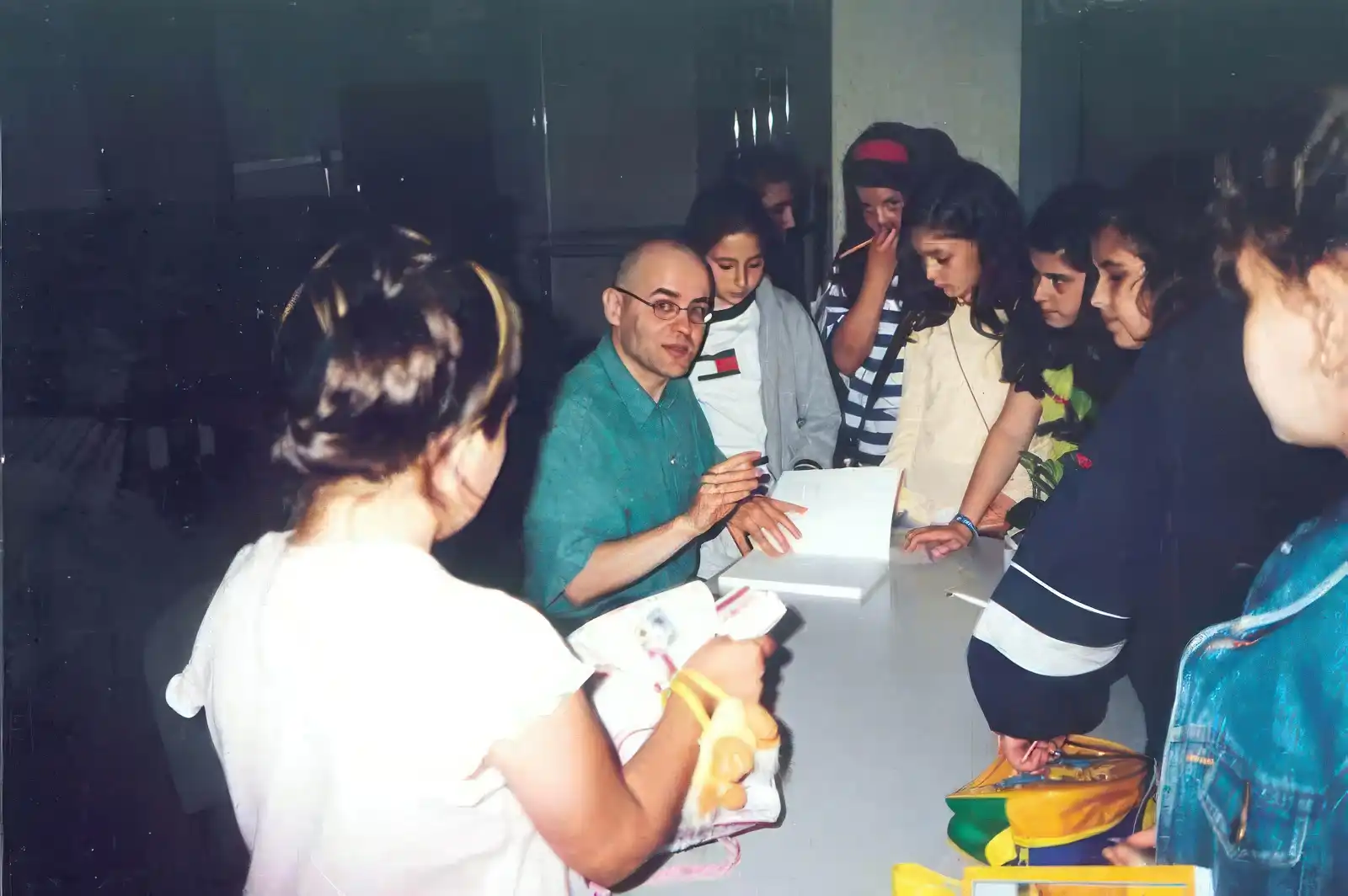

It all started innocently — with a few signed books at the Spring Book Fair in Sofia. “A calm beginning,” I told myself. Mistake! On May 20th, I found myself in the middle of a fan club made up of 30 mini-volcanoes, spewing questions, ideas and — oh yes — firmly claiming that The Ghost Forest is better than Harry Potter. I nodded wisely, scribbled that somewhere in my heart, and moved on.

On the 21st — boom! — Bulgarian National Television decided I was worth a short feature. The presenter hadn’t heard of the book, but turned out to be incredibly likeable. On the 22nd, I was already dashing toward Plovdiv, where the librarians had more energy than the kids. One autograph here, two smiles there — and suddenly they were promising me they'd be waiting impatiently for the second book.

Then came May 24th — Veliko Tarnovo and my hometown, Preslav. Students, teachers, old friends — everyone was happy I was home. And me? I was exhausted, but happy.

2001: A Bookish Odyssey

Pages, Kids, and a Dash of Chaos!

Ghost Park

Two years later, back on the road. I’m no longer just a guest — the books get there ahead of me. In Sofia, a familiar scene: book fair, signatures, puzzled passersby asking, “Who is this guy, and why won’t the line end?”

In Plovdiv, the librarians greet me like a rock star. Before I can even say “Hello,” they’re already holding the new book, flipping through the pages, quoting lines to me. The kids? They just dive straight into the shared excitement.

Shumen? Oh, there I’m in for a real surprise — the librarians not only know my stories, they might be even bigger fans than the students. They ask questions, dig for answers, pitch new ideas. “When’s the third book coming?” someone asks.

On the way back to Sofia, I’m tired — but I know now: it’s not just kids who love fairytales. And the third book? Hm… looks like I’d better hurry up.

2003: Return to the Fairytale Reality

More Books, More Fans, More Surprises!

Ghost Desert

Two years after my last tour, things are no longer the same. The second book won the award for Best Children’s Book of 2003 and… made it into school textbooks! I had no idea I’d become an “official” author.

Then came a surprise from Sofia — the founders of the first private German-language school decided my books were perfect for their curriculum. And so, I was back on the road — Sofia, Plovdiv, Shumen. In Plovdiv and Shumen, the librarians, now die-hard fans, welcomed me like an old friend.

But the real excitement was in the school. Seeing my own books used in class — that’s another level! The children read them, discuss them, analyze them. “What happens next?” they ask.

Flying back home, I realize: I’m no longer just a guest author. My stories are now part of an entire generation’s childhood.

2005: From Storybooks to Schoolbooks

Fairy Tales Enter the Classroom!

Ghost Forest Heads to China

From the Translator

Zlatko Enev is a philosopher, and in his story, almost every chapter holds a kind of deep wisdom — but it’s always delivered with humor.

In the machine created by Heino, we see the unfeeling giant cloaked in the mantle of “reason” — it’s called “the market.”

In the ant kingdom, even though we’re in a miniature world, we can’t shake the feeling that we’ve seen it all before — and our soul stirs at the recognition.

Justa Diva appears in only one chapter, but her words reveal the entire essence of art.

The riddles in the eagle’s nest made me laugh while translating — but when the laughter stopped, I realized something profound: the logic of “the smart devours the stupid,” and the two little eaglets who don’t yet know how to fly but already rely on a computer to think for them…

This world is so different from mine — and yet so very close!

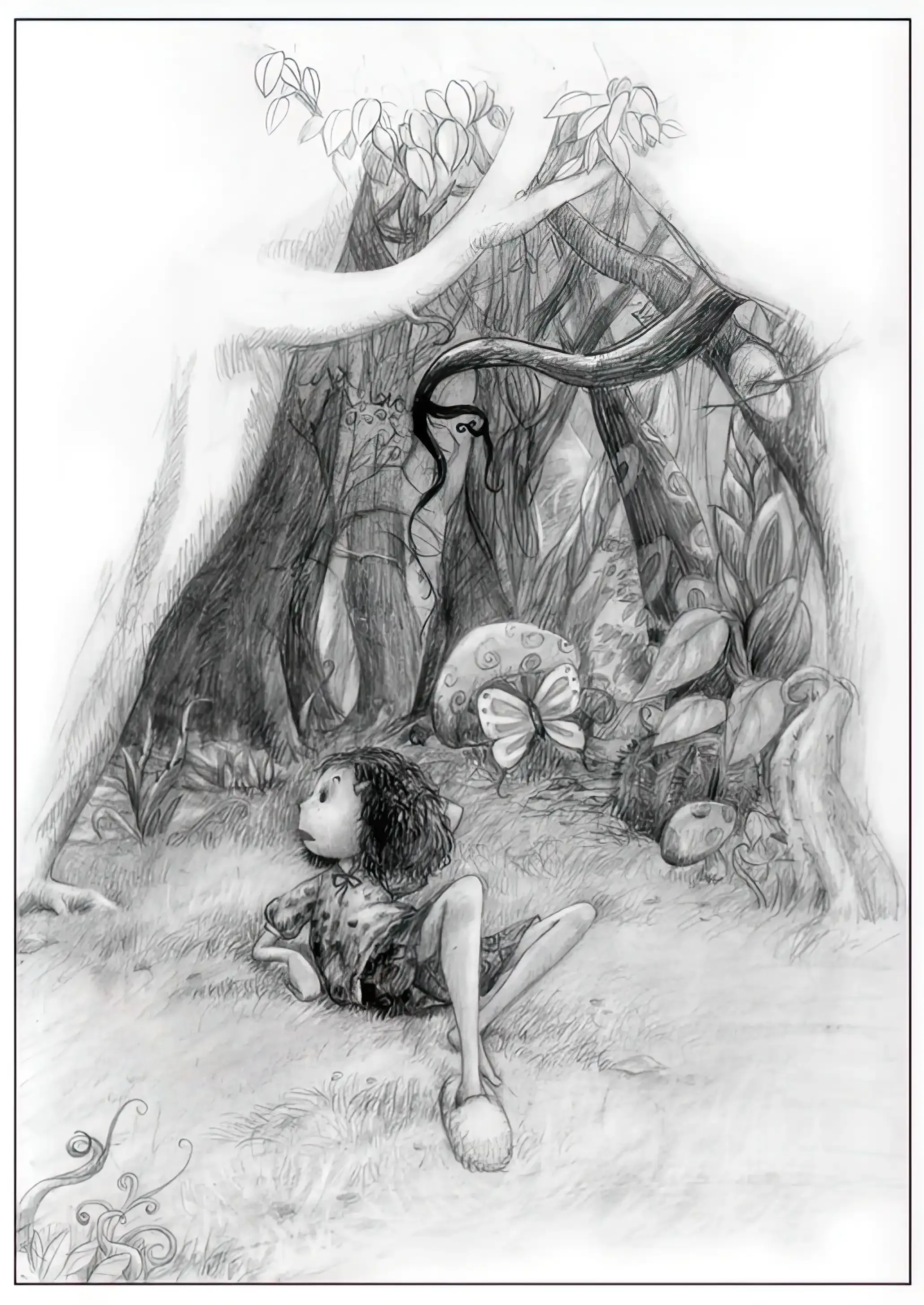

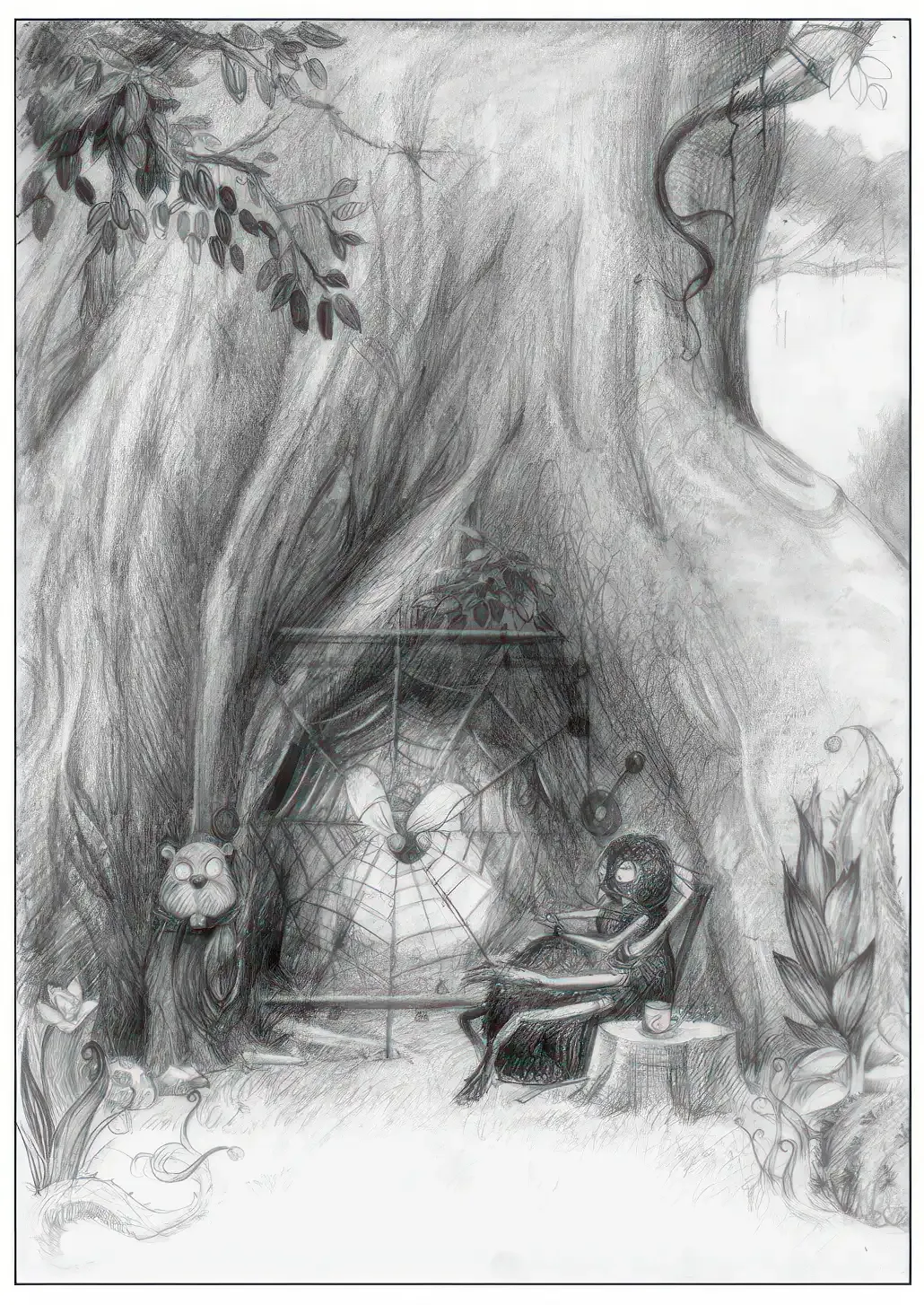

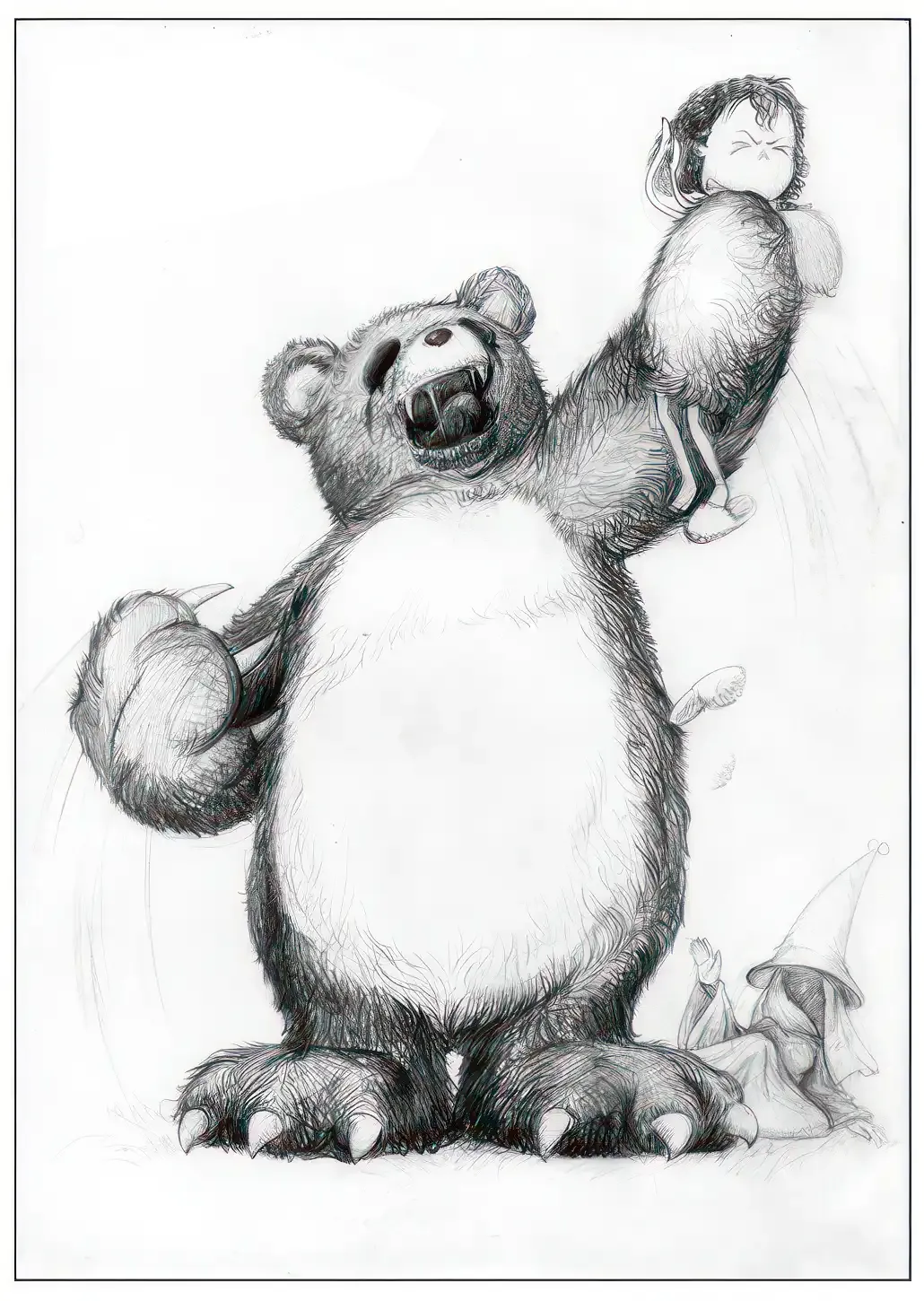

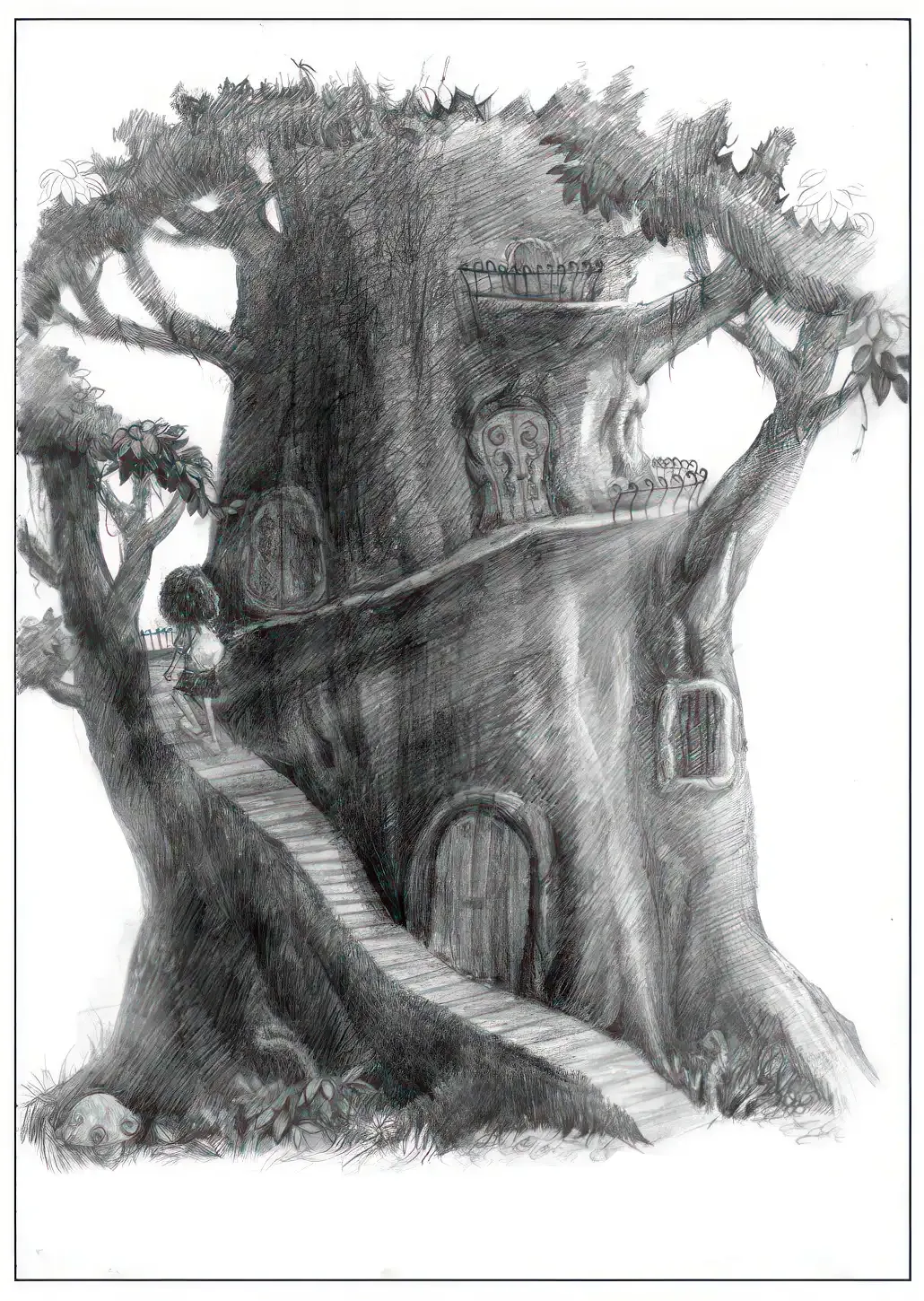

Illustrations for the Chinese Edition of Ghost Forest

Liberal Review

Liberal Review was born of restlessness. A buzzing, persistent feeling wouldn’t let its creator sit still. At first, it was only a whisper — a desire for connection, a challenge, an attempt to shake a slumbering world. But soon it became a voice, then a platform, and finally — a mission.

Alone, yet defiant, the writer — half exile, half observer — sifts through the noise of the internet, extracting meaning from the chaos. With each article, he shatters the cozy illusions that lull the mind. He is the gadfly, the irritant, the necessary sting against apathy.

The magazine is not a slick, commercial venture. It is stubborn, unpolished, entirely its own creature — created not for profit, but to provoke. And yet, it gathers more and more voices. Readers argue, discuss, return for more.

Does it change the world? Perhaps not. But it keeps the conversation alive. And sometimes, that is more than enough.

The Various Designs of the Magazine Over the Years

Requiem for Nobody

From the Author:

“Requiem for No One” – A Book I Couldn’t Not Write

This book wasn’t planned. It emerged from long-accumulated anger, from questions no one wants to ask, from stories that are conveniently forgotten. Requiem for No One is not an attempt to please. It is not an attempt to console or offer easy answers. It simply is.

For it, I was called a national renegade. I don’t know if that’s fair, but I do know this book was inevitable. There are no sermons in it, no salvation — only a man trying to understand the world around him without closing his eyes.

Does Bulgaria need such a book? Probably not. But now that it’s been written, the question becomes: is there anyone willing to read it?

And from the Readers:

“Requiem for No One” – Is the Humanist Rootless?

Like many book-loving Bulgarians born in the ’70s, I used to lament that Bulgaria still lacked a novel that meaningfully and convincingly captures the Transition. But reading Zlatko Enev’s Requiem for No One made me ashamed of my ignorance.

It turns out such a novel already existed — I simply hadn’t encountered it for the usual reasons. The Transition is an ambitious theme many have tried their hand at. Often, the pressure to say something big and important — something incomprehensible to those who didn’t live through it — drives authors either to over-ornament their stories or sink into brut-lit. Mr. Enev has avoided all the traps of the topic and drawn an impressively clear map of the dynamics of evil that began in 1944 and peaked during the Revival Process.

The novel begins with the forced renaming of the Pomaks, but it doesn’t present the Revival Process through the usual peephole. Instead, it shows it from the inside. The near-documentary precision with which Mr. Enev presents real information — about the torture cells, about party policy toward those to be deported — is striking.

Every character represents one of the inhumanities that occurred during the last 20 years of the 20th century. Some of the strongest portrayals are those reflecting the Revival Process. The renaming and the so-called “Big Excursion” form a knot the novel gradually unravels over the next two decades, tracing the characters’ paths across the border to Turkey, through the fall of the communist regime, organized crime, Kosovar brothels, and Germany.

Beyond the aesthetic pleasure of reading, the novel sheds strong light on Bulgaria’s political and social processes during this period. Through only the words and deeds of his characters, the author shows how the same people who sent Pomaks on a forced “excursion” later spearheaded organized crime, amassing wealth through trafficking, arms deals, and the breaking of the Yugoslav embargo.

The person who recommended the book to me warned me: “I’m not sure I should — it’s very heavy. There’s no love in this book.” And yes, it is heavy — at times unbearable to read, because of its documentary realism. As the reader turns each page, there’s no illusion: the perverse violence in the Kosovar brothels really happened; the torture in those cells was exactly as described; the subtle daily cruelties — just as real. Without slipping into gratuitous graphicness, the author uses plain words, and the sense of helplessness is suffocating.

But there is love in this book. The characters love one another — to the extent the circumstances allow. And because of the refreshing absence of moralizing, the reader senses that the author loves his characters, too. By the end, it becomes clear: Requiem for No One is not just about the Transition. It’s about abuser and victim. And those aren’t fixed roles — they’re masks we all wear, depending on the situation.

I can’t help but admire the compositional and structural skill with which Mr. Enev has arranged his novel. No character is underdeveloped. No scene overdone. The prose is rich, but refreshingly unpretentious. That was the first thing that struck me. Mr. Enev resists the urge to dazzle with eloquence. He generously gives voice to his characters, letting them drive the narrative logic. Together, their stories form a map of the evil we have lived — and continue to live.

Curious to learn more about Zlatko Enev beyond his work on Liberal Review and his books, I was stunned to discover how often he’s been labeled a “traitor,” “anti-Bulgarian,” and worse. I can only imagine what it’s like to be the center of such hostility for a humanist creative and civic position. But I believe it was worth it. Because of the result — Requiem for No One — I now have something I’ll one day give to my son, so he can understand the times that shaped his mother.

— Stanislava Churinskiene, writer

In Praise of Hans Asperger

It’s hard to write about this book. Because it’s brutal. If the reader doesn’t know the author and the family tragedy behind it, the text may be perceived as a literary monologue with masochistic overtones, spoken and published simply to test our emotional limits.

In fact, In Praise of Hans Asperger is a challenge to the boundaries of our ability to emit love — minute by minute, relentlessly, with undiminished strength, and with no hope of any improvement in the condition of the one we love.

This is a book about total and unanswered devotion — one human being’s commitment to another.

It all began 23 years ago. In the average Bulgarian-German family of Enev-Westphal, after the birth of their first child, Paul, came blue-eyed Lea — “a picture-perfect baby.” Calm, hungry, and rosy-cheeked. For two months. Then the nightmare began.

It started with inexplicable screams, triggered by an unknown cause. No one in the family suspected — and therefore the parents ignored — the first sign that their child might be “neurodivergent,” as it is delicately called today.

Much later it became clear that science still doesn’t know what causes autism. But one thing experts agree on: autism is not a disease, but a psychological condition with its own characteristics — traits that may evolve slowly, but fundamentally remain unchanged.

A diagnosis that feels like a sentence.

“Only when you stop fighting ‘against the illness’ and start fighting for your child,” says the author, “do you begin to grow. Only then do you gain peace, balance, normalcy, humanity. Before that, you’re just a ‘victim’ — of your own and society’s prejudices, wrapped in the fog of ignorance around this phenomenon.”

Twenty-three years! Lea’s only way of communicating with others was through rage and anger. Any change in her environment — even the smallest — was met with hostility and violent outbursts.

She couldn’t tolerate any disruption of routine. She learned to speak, though with confusion. But she never got tired of listening to favorite songs or watching beloved movies. Reading and writing came slowly — but she mastered the computer with surprising ease.

Doctors spoke of sensory overload. She refused to attend school, but loved to travel and found joy in changing landscapes. She didn’t enjoy speaking, but delighted in all forms of visual communication. Not only did she not feel lonely — she actually enjoyed solitude.

Today, Lea Enev is a beautiful and radiant young woman. The family is long since separated; Doreen and Zlatko paid a high price for their long walk through the fire. And the illness itself — it became a path.

And strangely: instead of frightening or repelling the reader with its brutal realism, Zlatko Enev’s book becomes a survival manual. It’s a painful, yet healing affirmation that human strength is inexhaustible — that for every trial life throws at us, it also gives us the energy to endure and emerge stronger, with fewer fears.

A remarkable confessional book: true and unflinching in its honesty, uplifting to the broken spirit, bitter yet filled with faith in the human within the human.

I doubt I’ll reread it anytime soon — maybe not in the next two or three years. But I’ll always keep it near, like a vial of antidote against the increasingly inhuman world we live in.

A book about the divine strength with which each of us can rewrite the plans of Fate.

— Neda Antonova, writer